Home | About Us | Services | Contact Us

Australia’s Northern Defence

Legendary Australian truck writer Bruce Honeywill recalls the days carting for Bellway during the construction of RAAF Base Curtin as part of Australia’s Cold War defence strategy.

UNCODE.initRow(document.getElementById(“row-unique-0”));

In the 1970s and 1980s, communication was nothing like today when driving trucks on long outback runs. There was more time to catch up with other truckies in roadhouses and find out news of the road. No mobile phones that give regular ‘stay awake’ conversations with mates and family. We had music from cassette tapes and perhaps the occasional radio news passing through a town. The heat and the dust shortened the life of a cassette tape to months. But the ‘dead’ tapes gave small amusements like cracking the plastic casing and letting the broken tape get caught by the wind. If you held the casing, the tape would run out straight back, straight as an arrow, along the side of three trailers, and at the back end, it would start to whip around like a run-over snake. Yeah, well … you amused yourself as best you could.

Those snippets of news were no more optimistic than they are today. The world lived under the clouds of the Cold War, and the news was about the latest possibility of nuclear war, what the Soviets most recently threatened, and what the Yanks and Brits reckoned they would do in return. On the global scale, it was like two mongrel dogs circling each other in a dusty street, sniffing, snarling, and growling and never quite with balls enough to start the fight.

That Cold War threatened Australia. We were caught with our national pants down in World War II, with our northern coastline largely unprotected when there was a real threat of invasion. It wasn’t going to happen again, according to the heads in Canberra.

It was that Canberra ‘decision making’ that had me driving through the Kimberley town of Derby in 1986 after a couple of years writing for Truckin’ Life. I was heading for a big contract site that would become a defence airstrip if the worst ever happened.

The RAAF Base Curtin, about 30km from Derby, was being built as part of Australia’s Cold War defence strategy. It was intended as a ‘bare base’, a facility that could be activated in times of a national security crisis. The logistics behind this base were clear. A nuclear-proof airstrip, proximity to Southeast Asia and its strategic significance were interesting enough. But for my trip, the story lay in the trucks and the men who drove them, hauling literally mountains of crushed material needed to make that airstrip a reality.

To create this airstrip with a landing zone with a nuclear-proof depth of more than 30m of reinforced concrete in such a remote part of the country required an incredible amount of material and manpower – not to mention the coordination between contractors like Leighton Engineering, Readymix, and Bellways. And making it all happen were the roadtrains.

As you drove into the Bellways camp, dust storms fogged the place as roadtrains rolled in for refuelling, checking, and maintenance. The camp was central, midway between the airstrip site and the Oscar Ranges that provided the limestone needed for construction.

The Bellways camp was a cluster of demountable buildings and a drive-through shed where the trucks were serviced. The haul cycle from site to range and back was a run of 340km, the trucks working 24/7 in two driver shifts of 12 hours, day shift and night shift.

The Bellways contract was to haul over half a million tonnes of aggregate from the Oscars to the delivery site. An assortment of trucks filled the various requirements of the contract: Kenworth, Mercedes-Benz and Scania. The kings of the run were the high-rise Mack Ultra-Liners, eight-wheeler body trucks hauling three trailers – at the time, the biggest road-registered outfits in the nation, the Western Australian regulations allowing for 40m overall length and a 142-tonne GVM. With the trucks taring in at just over 40 tonnes, it left a neat 100 tonnes of payload to be hauled.

I met the bosses at the Bellways camp and climbed into an Ultra-Liner cab with driver Wayne “Wally” Gater. Wally had been steering Bellways trucks for six years and knew the job like the back of his hand. We set out from the camp at daylight, the start of the day shift, with the deep grumble of the Mack V8 – back in the days when Macks had the personality and power of Yankee steel.

“Takes a couple of clicks to hit top gear,” Wally reckons, glancing over with a grin, “but once you’re there, she’ll keep going.” He wasn’t kidding. Wally let the engine lug down to 1400rpm on the climbs, allowing the raw torque to pull us over the top before it surged forward again, hitting 80km/h on the flats. Occasionally, he’d drop a gear to keep the momentum, but for the most part, the Ultra-Liner handled the load with steady confidence.

The Oscar Ranges, where the aggregate was quarried, looked like something out of another world, with jagged rocks and twisted boab trees set against a backdrop of endless Kimberley sky. These rocks were once part of a vast coral reef submerged under an ancient sea.

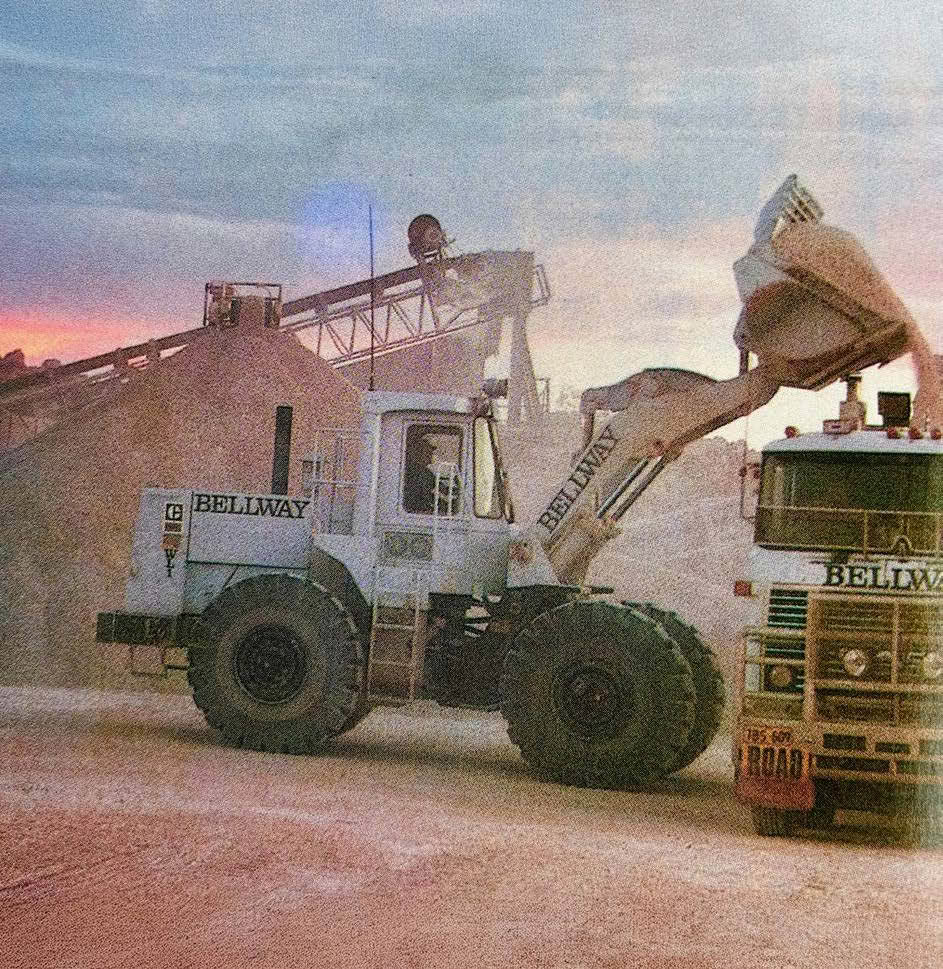

The quarry was a hive of activity, the dusty roar of crushers turning raw rock into the correct aggregate for the airstrip, loaders working around the clock to keep the trucks moving. Bellways’ big blue Cat loader worked non-stop, loading each truck with a weight accuracy that ensured the conditions of the WA permits were met and maintained. In less than 20 minutes, Wally’s truck was loaded and ready to go.

We pulled out of the quarry. I could feel the truck straining under the weight of the load, the big engine biting hard at the job in hand. Approaching the Great Northern Highway, the climb became steeper, the truck groaning under the effort. Wally dropped through the gears to make it through the gap in the Oscars, his hands steady on the wheel as the engine growled in response.

UNCODE.initRow(document.getElementById(“row-unique-1”));

Left: Loading a 100-tonne payload. Right: The trucks worked 24/7 in two-driver shifts.

UNCODE.initRow(document.getElementById(“row-unique-2”));

The trailers snaked behind us, disappearing into the dust, and the road ahead seemed to go on forever through the picture-postcard landscape of the Kimberley.

At night, the challenges were different; the darkness absolute, broken only by the truck’s halogen lights cutting through the blackness ahead. The road seemed to stretch on forever, and the isolation became very real.

Occasionally, another truck would appear on the horizon, its lights glowing like a distant beacon. The CB radio would crackle to life, a brief exchange of words between drivers. Respect was given to the Bellways roadtrains. Other drivers would give them the road, knowing full well the weight we were carrying and the challenge posed to keep the rig moving smoothly.

Through it all, the land remained an unforgiving constant. The dust was relentless, coating everything red. The sun beat down during the day, while the night brought a bone-chilling cold that seeped into the cab. But the job continued, shift after shift, the trucks rumbling along the highway, pushing through the challenges thrown at them by the Kimberley.

The RAAF Base Curtin lies quietly in the Kimberley landscape today, still ready for use if we ever face times of national emergency. Its role in Australia’s defence strategy is as critical today as it was during the Cold War. Things may have changed, but we still live in an uncertain geopolitical landscape. But the legacy of that time is not just in the base itself; it’s in the people who worked to build it, the towns like Derby that supported them, and the land that they moved through.

Looking back, sitting at a computer, the change in the outback and the types of contracts that built these remote parts of a beautiful country comes home to roost. Tourists, caravans, the distances, communication, trucks. How things have changed. Today, across Northern Australia, 55m, 130-tonne, four-trailer highway-legal outfits are common; 600 plus horsepower donks, even those automated transmissions – all a part of life.

You no longer see a mate coming towards you, pulling up. Two roadtrains stopped, taking up the road, sharing a couple of coldies from the Engel, swapping news and road conditions is unimaginable today with the restrictions placed on drivers and companies.

Those early bold moves by WA, in particular, introduced the large-spec multi-trailer outfits we take for granted today. They were pioneered in the West. Jobs like the construction of RAAF Base Curtin were the proving ground for the efficient roadtrain industry of today, an industry that keeps the remote northern half of Australia alive.

UNCODE.initRow(document.getElementById(“row-unique-3”));

UNCODE.initRow(document.getElementById(“row-unique-4”));

UNCODE.initRow(document.getElementById(“row-unique-5”));

The post Australia’s Northern Defence appeared first on NZ Trucking.